Monte Carlo Simulations: Class 2

Independent Study / Spring 2023

Francis L. Huang, PhD

huangf@missouri.edu

@flhuang

2023.01.25 / Updated 2023-04-22

Last week

- We talked about what simulations are

- Walked through an example of a simulation

- Talked about designing a simulation:

- Design: what conditions?

- Generate data: what's the data generating process?

- Analyze: ...

- Measure performance: ...

- Visualize: ...

Agenda:

- Revisit last week's discussion

- Using simulations to understand statistics better

- Running some t-tests from sampled data

- Understanding the standard error

- Transforming variables

- Basic univariate, nonnormal data generation

- Using the

samplefunction - Rolling two dice

- Simulating the Monty Hall problem (start)

Talked about generating data

If you obtained a correlation between two randomly generated, independent variables, how often would we expect to find statistical significance?

- Went through this one by one...

set.seed(123)x <- rnorm(100, 0, 1)y <- rnorm(100, 0, 1)cor.test(x, y) Pearson's product-moment correlationdata: x and yt = -0.49095, df = 98, p-value = 0.6246alternative hypothesis: true correlation is not equal to 095 percent confidence interval: -0.2435805 0.1483291sample estimates: cor -0.04953215Talked about how to obtain the statistic of interest, in this case, the p value

tmp <- cor.test(x, y)str(tmp)List of 9 $ statistic : Named num -0.491 ..- attr(*, "names")= chr "t" $ parameter : Named int 98 ..- attr(*, "names")= chr "df" $ p.value : num 0.625 $ estimate : Named num -0.0495 ..- attr(*, "names")= chr "cor" $ null.value : Named num 0 ..- attr(*, "names")= chr "correlation" $ alternative: chr "two.sided" $ method : chr "Pearson's product-moment correlation" $ data.name : chr "x and y" $ conf.int : num [1:2] -0.244 0.148 ..- attr(*, "conf.level")= num 0.95 - attr(*, "class")= chr "htest"tmp$p.value #is what we want[1] 0.6245623NANANANACreate a loop...Save the value

- This is a basic simulation, run the same test over a certain number of replications (in this case, 1,000: can be more)

reps <- 1000 #how many times to run thispvals <- numeric(reps) #create a containerset.seed(123) #for replicabilityfor (i in 1:reps){ x <- rnorm(100, 0, 1) y <- rnorm(100, 0, 1) tmp <- cor.test(x, y) pvals[i] <- tmp$p.value # saving the output in a vector}How many times should we expect this to be p < .05?

sum(pvals < .05) / length(pvals)[1] 0.053mean(pvals < .05) #or quite simply[1] 0.053NOTE: this should be based on our understanding of the test--

- Why .05?

NOTE: this should be based on our understanding of the test--

Why .05?

That's our type I error rate-- just by chance, we can expect to find something statistically significant-- even when there is no real difference!

- We can use simulations as a way to sharpen our understanding of our basic stat knowledge

Take another example: a one sample t-test

- Create a population of interest, let's say 30,000 students at a university

- We think that these students are higher ability (M = 105, SD = 15) than the average student (let's say M = 100, SD = 15)

- We only know what the 'average' student ability is

- If we were to sample \(n\) number of students from the population, how many would need to find statistical significant differences?

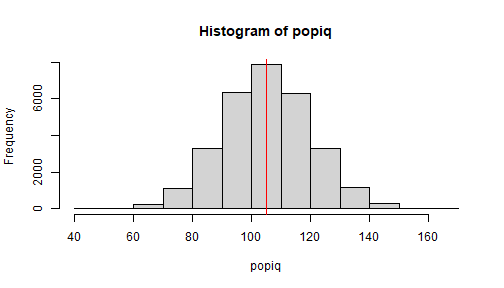

set.seed(246)popiq <- rnorm(n = 30000, mean = 105, sd = 15)This is another way of doing things... sampling from a population... which is what we generally do anyway.

This is our population... we are in control of this-- we know ("theta") \(\theta\) = true value

mean(popiq)[1] 105.0702sd(popiq)[1] 14.99542hist(popiq)abline(v = mean(popiq), col = 'red')

Now an important part of what we do is make inferences from a sample \(\rightarrow\) population

- We want to generalize from our sample to the population

- H0: Ability \(=\) 100

- H1: Ability \(\ne\) 100 (can also be one-tailed)

- How big a sample do we need to show this? (one sample t-test)

Source: Wikipedia

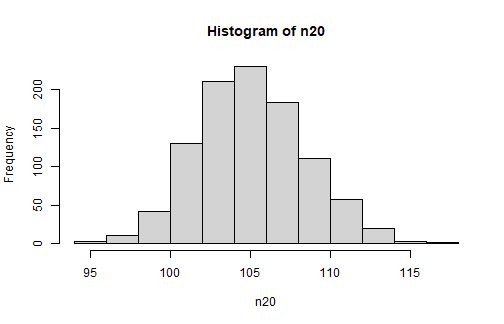

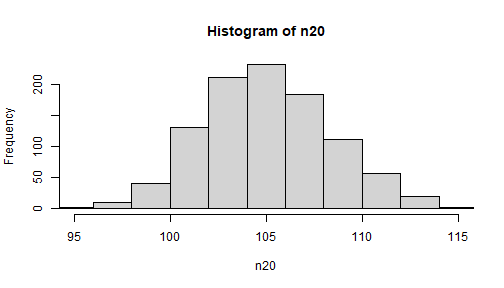

Take a sample: what if we use n = 20?

set.seed(100) #only doing this for my slidess1 <- sample(popiq, 20) # randomly sample 20 (without replacement)mean(s1)[1] 101.3393s2 <- sample(popiq, 20)mean(s2) ### all different of course[1] 102.4099s3 <- sample(popiq, 20)mean(s3) ### due to sampling variation[1] 111.9371s4 <- sample(popiq, 20)mean(s4)[1] 104.4906What if we run one-sample t-tests?

t.test(x = s1, mu = 100) One Sample t-testdata: s1t = 0.37384, df = 19, p-value = 0.7127alternative hypothesis: true mean is not equal to 10095 percent confidence interval: 93.84122 108.83731sample estimates:mean of x 101.3393t.test(x = s2, mu = 100) One Sample t-testdata: s2t = 0.51647, df = 19, p-value = 0.6115alternative hypothesis: true mean is not equal to 10095 percent confidence interval: 92.64343 112.17646sample estimates:mean of x 102.4099What if we take a 1000 samples of 20-- what would the distribution look like?

What if we take 1000 samples of 20-- what would the distribution look like?

reps <- 1000n20 <- numeric(reps)set.seed(123)for (i in 1:reps){ n20[i] <- mean(sample(popiq, size = 20))}mean(n20)[1] 105.0358sd(n20) ## what does this represent?[1] 3.32792What if we take 1000 samples of 20-- what would the distribution look like?

reps <- 1000n20 <- numeric(reps)set.seed(123)for (i in 1:reps){ n20[i] <- mean(sample(popiq, size = 20))}mean(n20)[1] 105.0358sd(n20) ## what does this represent?[1] 3.32792Although many times, our sample mean is higher than 100, there are also many occasions, due to sampling variation, where the mean is LESS than 100

hist(n20)

Remember, our t-test is \(\frac{\bar{x} - \mu}{SE_{\bar{x}}}\)

What is the standard error of the mean? Measure of imprecision-- since we only have a sample

$${SE}_{\bar{x}} = \frac{\sigma_{\bar{x}}}{\sqrt{n}}$$

15/(sqrt(20))[1] 3.354102## The SE is the standard deviation of the sampling distribution of meanssd(n20) ### close[1] 3.32792What if we ran a thousand t-tests?

reps <- 1000pv20 <- numeric(reps)set.seed(123)for (i in 1:reps){ pv20[i] <- t.test(sample(popiq, size = 20), mu = 100)$p.value}mean(pv20 < .05) #what does this represent?[1] 0.29What if we ran a thousand t-tests?

reps <- 1000pv20 <- numeric(reps)set.seed(123)for (i in 1:reps){ pv20[i] <- t.test(sample(popiq, size = 20), mu = 100)$p.value}mean(pv20 < .05) #what does this represent?[1] 0.29- This represents power to detect an effect (~29%)

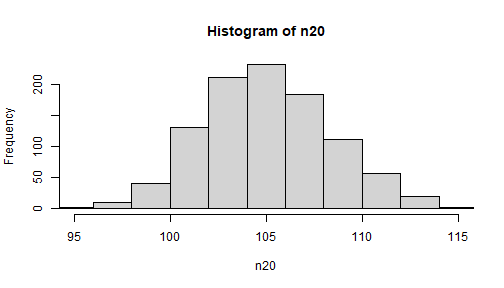

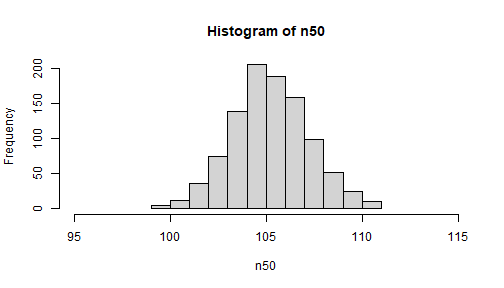

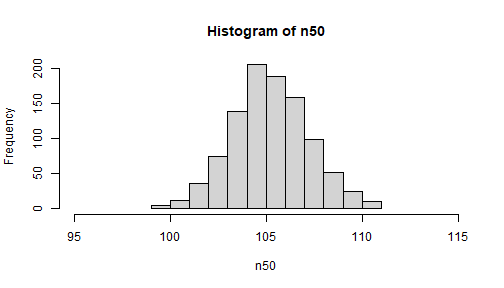

What if we take 1000 samples of 50-- what would the distribution look like?

reps <- 1000n50 <- numeric(reps)set.seed(333)for (i in 1:reps){ n50[i] <- mean(sample(popiq, size = 50))}mean(n50)[1] 105.2158sd(n50) ## what does this represent?[1] 1.987627NOTE: over repeated sampling, the mean of the means \(\hat{\theta}\) should converge on the true value \(\theta\) -- this means that the estimator is unbiased.

What is the theoretical SE?

15 / sqrt(50)[1] 2.12132- This is more precise compared to n = 20

Compare distribution of means

hist(n20, xlim = c(95, 115))

hist(n50, xlim = c(95, 115))

NOTE: the xlim option is specified so that the x-axes are the same in both (will not just use the default min and max which differ)

Compare distribution of means

hist(n20, xlim = c(95, 115))

hist(n50, xlim = c(95, 115))

NOTE: the xlim option is specified so that the x-axes are the same in both (will not just use the default min and max which differ)

- Many times, people think how accurate your estimate is depends on what percent of the population you sample (e.g., 10%, 50%)

- NOTE: the validity of the point estimate does not depend on the % sampled from the population-- we only have 50 out of 30,000 individuals w/c is < 1%.

What if we ran a thousand t-tests with n = 50, 70?

reps <- 1000pv50 <- numeric(reps)set.seed(123)for (i in 1:reps){ pv50[i] <- t.test(sample(popiq, size = 50), mu = 100)$p.value}mean(pv50 < .05) #what does this represent?[1] 0.675pv70 <- numeric(reps)set.seed(333)for (i in 1:reps){ pv70[i] <- t.test(sample(popiq, size = 70), mu = 100)$p.value}mean(pv70 < .05)[1] 0.809What if we ran a thousand t-tests with n = 50, 70?

reps <- 1000pv50 <- numeric(reps)set.seed(123)for (i in 1:reps){ pv50[i] <- t.test(sample(popiq, size = 50), mu = 100)$p.value}mean(pv50 < .05) #what does this represent?[1] 0.675pv70 <- numeric(reps)set.seed(333)for (i in 1:reps){ pv70[i] <- t.test(sample(popiq, size = 70), mu = 100)$p.value}mean(pv70 < .05)[1] 0.809- Not bad, with only n = 70, we can get a good estimate of the population mean!

Transforming variables

You can transform any random normal variable \(\mathcal{N}(0, 1)\) ('normally distributed with a mean of 0 and a variance of 1') by

- adding a constant (this will be the new mean)

- multiplying by a factor (this will be the new SD): e.g., \(\mathcal{N}(50, 10^2)\)

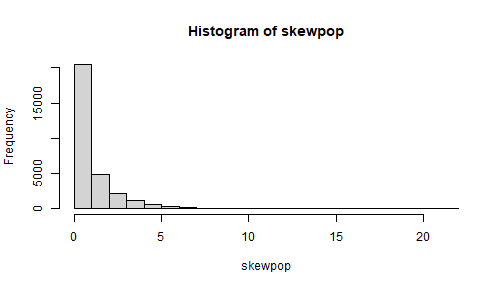

set.seed(312)test <- rnorm(10000) #m = 0, sd = 1mean(test)[1] -0.004945618sd(test)[1] 0.9886146test1 <- test * 10 + 50 # now called a t-statisticmean(test1)[1] 49.95054sd(test1)[1] 9.886146What if our population did not have a normal distribution? What would the sampling distribution of means look like? \(\chi^2\) distribution

set.seed(111)skewpop <- rchisq(30000, df = 1)## mean = df; var = 2dfmean(skewpop)[1] 1.002644var(skewpop)[1] 2.021265sd(skewpop)[1] 1.421712hist(skewpop)

Uniform distribution (all values are equally likely) is also common...

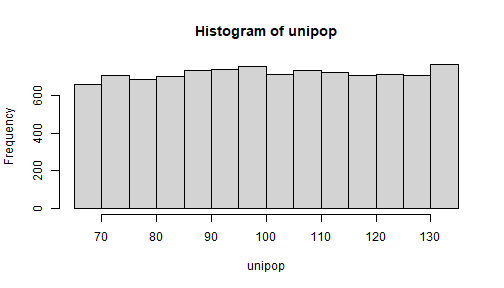

unipop <- runif(10000, 65, 135)# var = (b - a)^2 / 12; # mean = (a + b) /2mean(unipop)[1] 100.3927(65 + 135) / 2[1] 100var(unipop)[1] 403.724(135 - 65)^2 / 12[1] 408.3333sd(unipop)[1] 20.09288hist(unipop) NOTE:

NOTE: runif(1000) will generated values from 0 to 1 by default.

NOTE: all random numbers distributions are based on the random uniform distribution

All random number generator functions are based on RANUNI, because all distributions can be obtained from a uniform distribution according to a theorem of probability theory. The transformations from uniform to other distributions are carried out by the inverse transform method, the Box-Müller transformation, and the acceptance-rejection procedure applied to the uniform variates generated by RANUNI. Internally, SAS generates only uniform random numbers with RANUNI and transforms them to the desired distribution.

Fan et al. (2002). SAS for Monte Carlo studies: A guide for quantitative researchers. p. 42

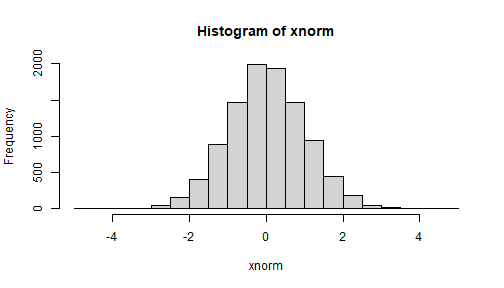

Using the faux package... transform uni to \(\mathcal{N}\)

xnorm <- faux::unif2norm(unipop)hist(xnorm)

The faux packages has many functions to transform distributions. You can view the code as well how this is done.

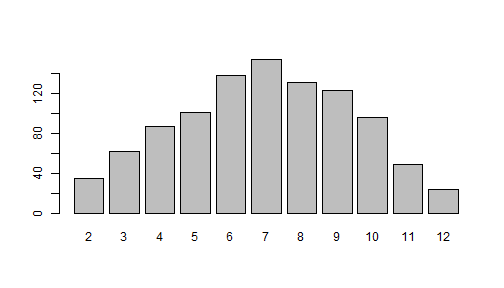

Rolling two dice: what's the most common roll?

Uniform distribution, 1 to 6

- Test this out first:

d1 <- sample(1:6, 1)d2 <- sample(1:6, 1)tot <- d1 + d2tot[1] 9Catan board game example...

- Rolling for resources:

Source: https://www.boardgameanalysis.com/what-is-a-balanced-catan-board/

Do this 1,000 times

rolls <- numeric(1000)set.seed(123)for (i in 1:1000){ d1 <- sample(1:6, 1) d2 <- sample(1:6, 1) rolls[i] <- d1 + d2}Examine frequencies and plot this out

sjmisc::frq(rolls)x <numeric> # total N=1000 valid N=1000 mean=6.96 sd=2.46Value | N | Raw % | Valid % | Cum. %-------------------------------------- 2 | 35 | 3.50 | 3.50 | 3.50 3 | 62 | 6.20 | 6.20 | 9.70 4 | 87 | 8.70 | 8.70 | 18.40 5 | 101 | 10.10 | 10.10 | 28.50 6 | 138 | 13.80 | 13.80 | 42.30 7 | 154 | 15.40 | 15.40 | 57.70 8 | 131 | 13.10 | 13.10 | 70.80 9 | 123 | 12.30 | 12.30 | 83.10 10 | 96 | 9.60 | 9.60 | 92.70 11 | 49 | 4.90 | 4.90 | 97.60 12 | 24 | 2.40 | 2.40 | 100.00 <NA> | 0 | 0.00 | <NA> | <NA>barplot(table(rolls)) Many ways to roll a 7:

Many ways to roll a 7:

- 6-1 / 1-6

- 3-4 / 4-3

- 5-2 / 2-5

This is probably a good place to talk about functions in R...

- Things that do something in R are functions:

functionname() - This is just an example of a function with no options available

roller <- function(){ d1 <- sample(1:6, 1) d2 <- sample(1:6, 1) d1 + d2}#run the functionroller() #it works![1] 3roller()[1] 8When you run it, need the (). If not, you will just see the code.

Can use the function 1,000 times

out <- replicate(1000, roller())str(out) int [1:1000] 9 4 9 8 8 11 5 5 7 8 ...barplot(table(out)) Get the same results!

Get the same results!

The sample function is pretty useful

- Let's say you have a population that is 50% White, 20% Black, 15% Hispanic, and 15% Other

race <- sample(c('w', 'b', 'h', 'o'), 100, replace = TRUE, prob = c(.5, .2, .15, .15))sjmisc::frq(race)x <character> # total N=100 valid N=100 mean=3.02 sd=1.19Value | N | Raw % | Valid % | Cum. %-------------------------------------b | 18 | 18.00 | 18.00 | 18h | 15 | 15.00 | 15.00 | 33o | 14 | 14.00 | 14.00 | 47w | 53 | 53.00 | 53.00 | 100<NA> | 0 | 0.00 | <NA> | <NA>- Can also use it for bootstrapping

- Or you can create a population (like what we did) and sample from it

Simulation basics: Monty Hall Revisited

- As mentioned, recently reminded about this by the feature article in Chance magazine

Marilyn vos Savant, in her weekly “Ask Marilyn” column in Parade magazine, answered a reader’s question about a game show very similar to “Let’s Make a Deal”:

“Dear Marilyn: Suppose you’re on a game show, and you’re given the choice of three doors. Behind one door is a car, the others, goats. You pick a door, say number 1, and the host, who knows what’s behind the doors, opens another door, say number 3, which has a goat. He says to you, ‘Do you want to pick door number two?’ Is it to your advantage to switch your choice of doors?” –Craig F. Whitaker.

Source: https://chance.amstat.org/2022/11/monty-hall/. On another note, she was born in St. Louis, MO in 1946.

A lot has been written about this (even book/s on the topic):

At first glance, the solution seems pretty straightforward. With two doors left, one of which has the car behind it and the other a goat, chances must be 50-50. In other words, it should make no difference at all whether you switch doors or stick to the door of your initial choice. But vos Savant replied: Dear Craig: "Yes, you should switch. The first door has a 1/3 chance of winning, but the second door has a 2/3 chance."

Source: Wikipedia; Chance magazine

Many people could not believe her answer (from Chance Magazine)

She received more than 10,000 letters from readers of her column, the vast majority of whom were absolutely convinced that she was wrong

One reader ... wrote: “…I am sure you will receive many letters on this topic from high school and college students. Perhaps you should keep a few addresses for help with future columns.” In other words, vos Savant, although once listed in the Guinness Book of Records for her exceptionally high IQ, supposedly did not have the slightest understanding of probability.

Even the Hungarian mathematical genius Paul Erdős initially thought vos Savant’s solution was impossible

To convince people: She called on math classes across the United States to take a die, three paper cups, and a penny; turn the cups over; and hide a penny under one of the cups. Then the students—one being the ignorant contestant, another the knowing host—should simulate the game, repeating each of the two strategies, switching and sticking, 200 times [LET'S DO THAT!]

Before we get into the details of writing a simulation, let's understand first WHY her answer is correct

- Let's write out all the possible combinations of the first choice (picking and sticking with the door)

#initial choiceIC <- rep(1:3, each = 3)#winning doorWD <- rep(1:3, 3) #Win (1) if the same else lose (0)res <- ifelse(IC == WD, 1, 0) xx <- data.frame(IC, WD, res)xx IC WD res1 1 1 12 1 2 03 1 3 04 2 1 05 2 2 16 2 3 07 3 1 08 3 2 09 3 3 1mean(xx$res)[1] 0.3333333(cont.) what if we switch doors? This is my way of understanding this!

- NOTE: the host will only open a door that has a goat-- the host will not open a door with a car! [OD = open door; SD = switched door]

sw IC WD OD SD res1 1 1 2/3 3/2 02 1 2 3 2 13 1 3 2 3 14 2 1 3 1 15 2 2 1/3 3/1 06 2 3 1 3 17 3 1 2 1 18 3 2 1 2 19 3 3 1/2 2/1 0mean(sw$res)[1] 0.6666667- You will only lose if you chose correct the first time! If you chose wrong (and switch), you will win.

- Your chance of being wrong is 2/3rds as well.

So how do we go about programming this?

Source: https://xkcd.com/1282/

The no-switch condition

noswitch <- function(){ ic <- sample(1:3, 1) wd <- sample(1:3, 1) ifelse(ic == wd, 1, 0) #the last value is returned by the function}res <- replicate(10000, noswitch())mean(res)[1] 0.3297Once you start the switchdoor condition, you may want to simulation opening a door and then checking if the switched door is a winning door

This may help check which doors to remove: https://www.statology.org/remove-element-from-vector-r/